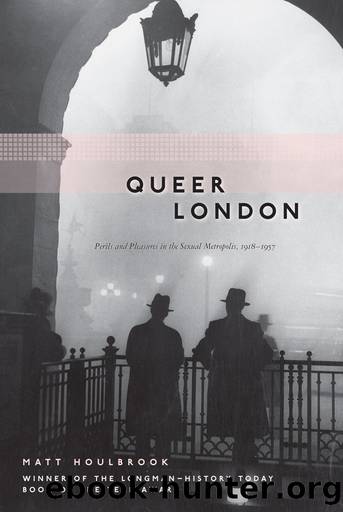

Queer London by Matt Houlbrook

Author:Matt Houlbrook [Houlbrook, Matt]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History

ISBN: 9780226354620

Google: wyV9ejoQRS4C

Barnesnoble:

Goodreads: 467218

Publisher: University of Chicago Press

Published: 2005-09-03T00:00:00+00:00

PART 4

POLITICS

9

SEXUAL DIFFERENCE AND BRITISHNESS

KARLâS STORY

In June 1937 the Danish milliner Karl B. left Paris for London. At Croydon Airport he was met by an immigration officer and turned back. This was not the first time Karl had been refused entry to Britain. Initially barred in 1933, he was denied permission to land at Harwich in 1934 and had an application to return declined in 1936. âHe is a sex pervert,â noted an official from the Home Office Immigration Branch, âhe should not be allowed to land in the United Kingdom.â1 While there was no suggestion that Karl had been prosecuted for a sexual offence, in 1933 officers found the addresses of several Government officials on him and suspected that his âvisit was for the purpose of blackmail.â He was, further, âin possession of a considerable number of letters written by [Arthur P., his business partner] couched in affectionate terms which left little doubt that both persons were moral perverts.â Arthur visited the Harwich Immigration Office and Home Office, seeking permission for his partner to land. He was unsuccessful.2

Why was Karl B. kept out of Britain? We might widen the question, since if Karl was excluded from Britainâs territorial boundaries, queer men in general were positioned beyond the imagined boundaries of Britishness. In part, this was a physical process, embodied in the criminalization of particular queer practices and the logic of imprisonmentâremoving a source of danger from the community. Exclusion was also a cultural process, emblematized by the construction of sexual difference and queer urban culture as disturbance, immorality, and threat. These were, indeed, mutually constitutive. The sexual offences laws were underpinned by ideas of the queerâs transgressive character, which were, in turn, reinforced by the operations of those laws. Again: why were queer men legally and culturally excluded from British society? Rather than identify an innate hostility towards the âsexual pervertââthe ahistorical category of âhomophobiaââwe need to understand the public meanings of âhomosexualityâ in the early twentieth century. What negative attributes was it invested with? Why was the sexual deviant deemed so threatening as to warrant the forms of regulation explored above?

The answers lie in the law itself. If official surveillance exercised a profound influence on the cultural and geographical organization of queer urban life, it also exercised a similar influence on official and public knowledge of that world. While many queans flamboyantly carried their difference into Londonâs streets, most men sought to avoid the public gaze. It was only through their encounters with the police that they were, reluctantly, drawn into that gaze. Whether through the nightclub raids that initiated the spectacular âpansy casesâ of the 1930s or the everyday patrols behind the stories of errant clergymen and cottaging laborers appearing each week in the News of the World, police operations were central to the process through which queer lives were uncovered, codified, and named for popular consumption.

Policingâs importance to this process was reinforced by the conventions of newspaper reportage. In contrast to the ânew journalismâ of the

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Sex Workers As Virtual Boyfriends by Joseph Itiel(205)

A Trans Man Walks Into a Gay Bar: A Journey of Self (And Sexual) Discovery by Harry Nicholas(181)

Despite All Adversities by Lema-Hincapié Andrés;Castillo Debra A.;(176)

A History of Women in Men's Clothes by Norena Shopland;(167)

Transgender Behind Prison Walls by Baker Sarah Jane Stockwell Pam(166)

One Marriage Under God by Melanie Heath(158)

Transgender Employees in the Workplace by Jennie Kermode(157)

Substance Use Disorders in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Clients by Sandra Anderson(152)

Visions of Sodom by H. G. Cocks(149)

Lesbian Doms: 10 Women Describe Their Most Memorable Lesbian Domination Experience by Foster Kendra(149)

Confronting Religious Denial of Gay Marriage by Wallace Catherine M.;(147)

Queer TV China by Zhao Jamie J.;(146)

Consumed by Desire (Central Park South Book 1) by Bianca Vix(144)

Who's Who in Contemporary Gay and Lesbian History Vol.2 by Robert Aldrich Garry Wotherspoon(141)

Lesbian Mothers by Ellen Lewin(136)

Mobile Orientations by Nicola Mai(130)

A Practical Guide to Searching LGBTQIA Historical Records by Norena Shopland(129)

She and Her Pretty Friend by Danielle Scrimshaw(129)

My White Best Friend by Rachel De-lahay(126)